From Content Creation to Knowledge Architecture: What We Learned Building an AI-Native Workflow

The Meeting

I was in an online meeting with a high-stakes client when everything clicked. I had spent weeks preparing an outline for a complex Redbook, but the client’s feedback was significant enough to require a significant restructure. In the old world, this would have meant days or weeks of rework and likely a follow-up meeting. Instead, I fed the feedback into my AI system and completely reworked the outline in real-time. The client was impressed. I was relieved. But more importantly, I realized we had crossed a threshold where late had become the same as not at all.

That moment crystallized something I’d been wrestling with for months: my team wasn’t just experimenting with AI tools anymore. We were rebuilding the entire knowledge architecture of technical publishing.

The Framework That Changed My Thinking

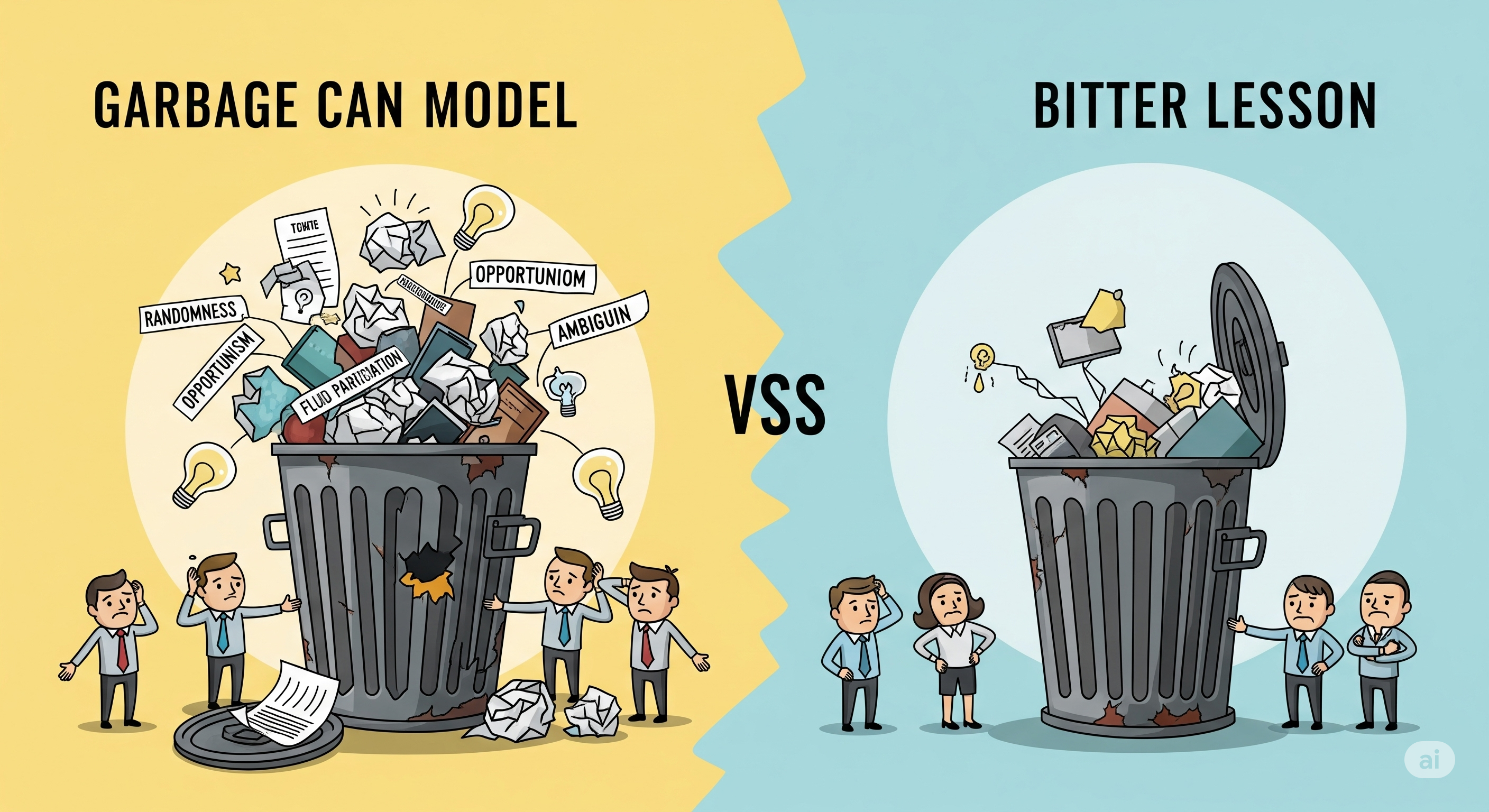

A few weeks later, I read Ethan Mollick’s newsletter “The Bitter Lesson versus The Garbage Can” that perfectly articulated the tension I was experiencing. Mollick describes two competing models for how organizations work and how AI might fit into them.

The Garbage Can Model views organizations as chaotic systems where problems, solutions, and decision-makers get “dumped together,” and decisions happen when these elements collide somewhat randomly rather than through fully rational processes. It’s a world of unwritten rules, bespoke knowledge, and complex undocumented processes - exactly what we discovered when we started mapping our own workflows.

The Bitter Lesson, coined by AI researcher Richard Sutton, observes that in AI development, elegant solutions encoding human expertise are consistently outperformed by brute force computational approaches. Chess programs that encoded centuries of human chess wisdom were eventually beaten by systems that simply learned by playing millions of games against themselves. The “bitter” reality is that human understanding of problems, built from lifetimes of experience, often matters less than just giving AI enough computational power and letting it figure out solutions on its own.

Mollick’s insight is that we’re about to discover which model applies to organizational work: Are teams and orgs like chess games that will yield to computational scale, or are they fundamentally messier systems that require understanding and mapping all that organizational chaos?

This framework became the lens through which I understood my team’s AI transformation journey.

“We Thought We Were Solving Content Creation…”

The Personal AI Honeymoon

Like many technical leaders, I started with individual experimentation. My Ollama + Open WebUI local setup was perfect for my workflow. I could research, outline, and refine content at unprecedented speed. The AI understood my writing style, could synthesize complex technical concepts, and helped me maintain consistency across documents. I was hooked.

But here’s the thing about individual AI wins: if it doesn’t scale, it doesn’t matter. My local setup solved my problems, sometimes brilliantly. But it did nothing for my team with cumulative hundreds of years of deep software and hardware experience but little background in information architecture or generative AI.

The Scale Reality Check: When Tailwinds Meet Implementation Reality

The irony wasn’t lost on me. We had every possible tailwind behind AI adoption: clear top-down mandate from leadership, proven POCs showing immediate value, a team excited about the possibilities, and a business environment where our clients literally couldn’t wait for traditional timelines. The stars were aligned for transformation.

Then we hit the wall of actual implementation.

The cost reality is real, and nebulous. My free local setup was perfect for experimentation, but scaling to 15 people means choosing between expensive enterprise AI subscriptions or complex technical infrastructure that our team can’t manage. Even with management approval, the math gets sobering quickly: tokens aren’t free, and when you’re processing hundreds of pages of technical content through multiple personas and revision cycles, costs compound fast.

The training burden was even more daunting. Each team member needed to understand not just how to prompt effectively, but how to think about tokenization limits, model capabilities, and workflow integration. “Just use ChatGPT” isn’t instructions: it is the beginning of a comprehensive education program we hadn’t budgeted time for.

Mapping the Garbage Can - Discovering What We Actually Do

From Publications to LEGO Blocks

When we started mapping our actual content creation process, we discovered we had been fundamentally misunderstanding our own work. For decades, our subject matter experts (SMEs) and engineers came together to write complete publications. This approach required writing skills many lacked and often failed to meet users where they actually were.

The AI-native approach is forcing us to think differently. Instead of complete documents, we are in the process of creating atomic units of content - modular, LEGO-like pieces that can be restructured and adapted for length, tone, and complexity based on specific user personas and contexts. A single piece of SME knowledge can now serve CTOs seeking strategic overview, developers needing implementation details, and architects requiring system integration guidance.

The Invisible Complexity Problem

What looked simple in our initial outline revealed layers of hidden complexity as we scale within a large enterprise. Take something as seemingly trivial as trademark usage. In our publications, we might have 350+ instances of trademark symbols and 75 different product names. The rule seems simple: use ™ on first usage of a product name, never after, and understand when “IBM” is part of a product name versus standing alone.

Simple rule, right? Wrong. This requires contextual reasoning, memory across document sections, and understanding of product naming conventions that have evolved over decades. Multiply this by dozens of similar “trivial” compliance and accuracy requirements, and you begin to understand why refinement has become our primary bottleneck.

The Expert Paradox - When Decades of Experience Meets Probabilistic Output

Making Experts Feel Like Novices

Perhaps the most challenging aspect of building an AI-native workflow isn’t technical, it’s human. We are asking people who have built careers as the “go-to person” for complex technical explanations to trust AI systems. It’s hard to take experts with decades of experience and show them processes that seemingly trivialize and undermine their accumulated knowledge.

The resistance isn’t about technology adoption. These are people who’ve navigated countless platform migrations and tool changes. The challenge is deeper: we are fundamentally changing what expertise means in our workflow.

The Trust Problem with Probabilistic Systems

Our team comes from deterministic code backgrounds. When you write software, the same input produces the same output, every time. Generative AI introduced something foreign to our engineering mindset: probabilistic output that could be right 95% of the time but wrong in ways that were hard to predict or catch.

This isn’t just about accuracy. It’s about workflow confidence. Time spent prompting and validating AI output is time taken away from existing processes that worked. The question becomes: how do you build trust in systems that are fundamentally non-deterministic when your team’s expertise is built on predictable, repeatable processes?

If It Doesn’t Scale, It Doesn’t Matter

The Individual vs. Team Success Gap

We kept running into the same pattern: individual team members would solve specific problems with AI, get excited about the results, then struggle to share that success with the broader team. One person would develop an elegant prompting strategy for technical specifications. Another would create a workflow for persona-based content adaptation. A third would solve our citation consistency problem.

But individual solutions, no matter how brilliant, often created more problems than they solved at team scale. Different approaches to the same problems led to inconsistent outputs. Undocumented prompting strategies became tribal knowledge that didn’t transfer. Personal AI setups that worked perfectly for one person failed for others with different technical environments or working styles. Solving the same problem 15 different ways equals not solving it at all.

Speed + Direction = Velocity

Early in our AI adoption, we got caught up in the raw speed gains. AI could generate first drafts in minutes instead of days. It could restructure content instantly. It could adapt tone and complexity on demand. But speed without direction is just motion, and motion without purpose doesn’t create value.

We learned to think about velocity instead: speed plus direction. This meant building quality gates that didn’t become bottlenecks, integrating UX research as part of the process rather than a stopping point, and always ensuring that faster meant better for our end users, not just more convenient for us.

What We’re Learning - The Bitter Lesson for Knowledge Work

Which Approach Is Winning?

Months into building our AI-native workflow, we’re seeing evidence for both sides of Mollick’s “Bitter Lesson vs. Garbage Can” debate. Some problems yield beautifully to the Bitter Lesson approach - define good outputs, provide examples, let AI figure out the path. Our persona-based content adaptation works this way: we don’t encode rules about how to write for CTOs vs. developers, we use exhasutive research that has gone into persona development and turn that into effective communication for each audience.

But other problems stubbornly require the Garbage Can mapping approach. Our trademark compliance, citation standards, and technical accuracy requirements need explicit rules and systematic checking. The AI can apply these rules once we’ve encoded them, but it can’t reliably infer them from examples alone.

Advice for Other Technical Teams

If I were advising another technical team starting this journey, here’s what I’d tell them to prepare for:

-

You’re not adopting AI tools. You’re rebuilding your knowledge architecture. Plan accordingly. The technical challenges are solvable; the conceptual and organizational challenges are where you’ll spend most of your energy.

-

Individual AI wins can actually create team problems if they’re not designed for scale from the beginning. Resist the temptation to let everyone solve their own problems with AI. Instead, focus on building systems that work for everyone.

-

Your experts aren’t becoming less valuable, their value is changing. Help them see the transition from “person who explains complex things” to “person who architects knowledge systems.” It’s a promotion, not a replacement.

Conclusion: The Game We’re Actually Playing

We started thinking we were playing a content creation game: faster drafts, better outlines, more consistent formatting. We discovered we were actually playing a much bigger game of rebuilding how technical knowledge gets created, validated, and delivered in an age when late is the same as not at all.

The jury’s still out on whether knowledge work will follow the chess pattern, yielding to computational scale and general approaches, or prove to be something fundamentally messier that requires human understanding and systematic process mapping. Based on our experience so far, I suspect it’s both. Some aspects of knowledge work will yield beautifully to the Bitter Lesson approach, while others will require careful mapping of the Garbage Can.

What I’m certain about is this: teams that figure out how to build AI-native workflows while preserving human expertise and institutional knowledge will have significant advantages in markets where speed and accuracy both matter. The companies betting on either pure automation or pure human process are missing the hybrid opportunity.

We’re still building, still learning, still discovering new layers of complexity in problems we thought we understood. But every meeting where we can reshape an entire project approach in real-time reminds us why this transformation, difficult as it is, isn’t optional anymore.